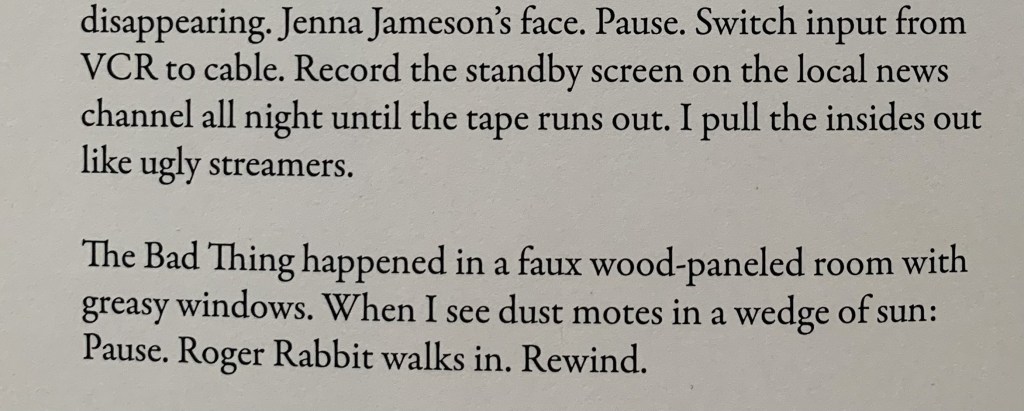

At the direct center of this sharp, 13-page stapled chapbook is a poem titled “Analog.” Circling around the motif of spliced and “gutted” VHS tapes, Canese Jarboe constructs an elliptical, fragmented narrative of childhood trauma that collides with a pastiche of analog moments ranging from Disney movies, to pornography, to recordings of televised cattle auctions:

We never learn precisely what “The Bad Thing is,” but within this context of this poem—and the chapbook more broadly—it pulsates like a black hole around which memory and lyric momentum swirl. Given that Jarboe’s work occupies a decidedly rural, agrarian landscape, the choice to place a poem titled “Analog” at the center of the text is significant: media, particularly in the pre-digital era that the poem appears to document, functions (like the lyric itself) as a way out—a bridge from an otherwise isolated geography to distinctly other spatial and ontological possibilities: queer desire and adult sexuality (“I had crossed the threshold”); military bootcamp; the Californian high school of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. Within the splicing of VHS tapes, there is a world-making at play—Jarboe invokes the movement of linear time and beckons its collapse: “All that is left is the feeling outside the frame.”

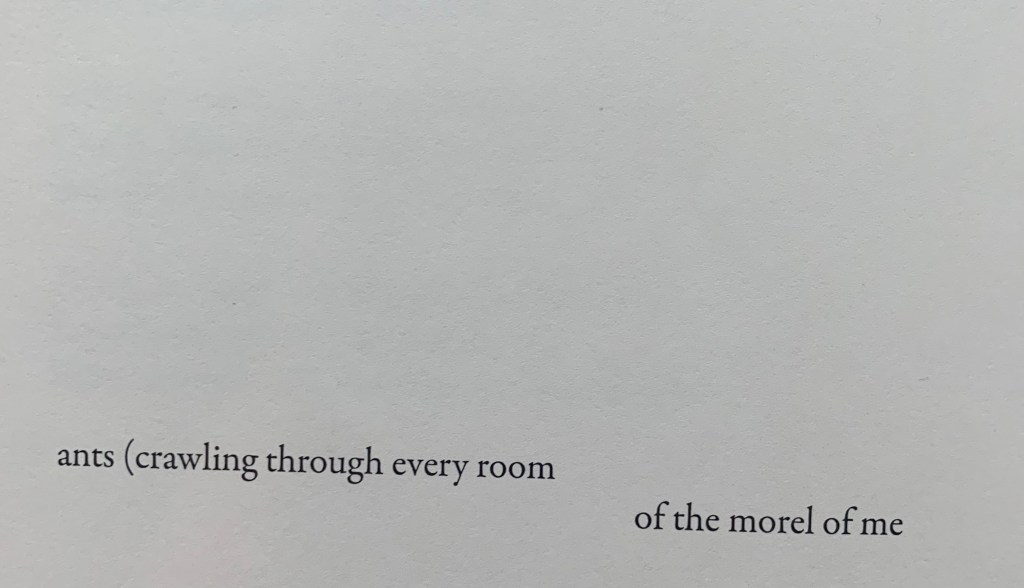

That last line—the tension between what “the frame” does and does not hold—mirrors Jarboe’s larger approach to lyric containment throughout this text. Bookending the more formally regulated pieces (like the appropriately titled “Pastoral,” a loosely iambic pentameter poem in tercets) are floaty, several-line pieces that offer a strikingly literal imposition of “the natural” onto the body:

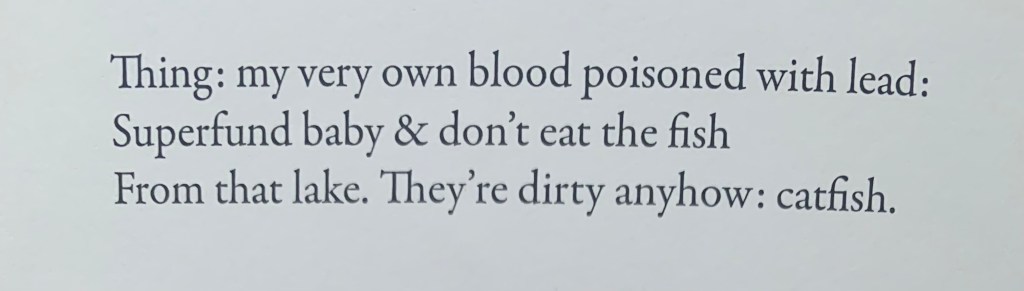

These moments in the chapbook, where the formal stability appears to pour over onto subsequent pages, are the ones that excite me the most. Because of its preoccupation with the rural—and its clear relationship to lineages of rural lyric experimentation (e.g. Frank Stanford, Lorine Niedecker)—I feel a deep affinity with Jarboe’s writing. While much of the rural writing I love takes a more explicitly adversarial relationship with the pastoral mode, one thing I find really striking about Jarboe’s work is that they place idealized natural beauty (e.g., “patches of white / Clover”) on the same plane of importance as lines that explicitly gesture towards the real ecological violences of the present:

This collision between the idyllic and the violent—properties that orbit around each other and occasionally collide—is remarkably identifiable to me, as someone who has lived in rural or small-town geographies for the most of my life. I’m writing this review from the South Hill of Ithaca, New York, with a superfund site a half-mile to the west and a giant waterfall a half-mile to the east. Jarboe’s chapbook begins by asking, “What if there is no wind.” And fortunately, there is: I feel it in these poems.

Leave a comment